Your Interactions with Students

The way you present yourself to students--vocal tone, gestures, location in room, rapport, posture, eye contact, etc.-- all make a difference in how your students will respond, pay attention, and interact with you, peers, and the material. Below are things to consider when leading a class.

Interaction with Student

- Make sure to face the students and check in on their understanding. Look for signs of confusion, distraction, or frantic writing to keep up, then change what you are doing accordingly.

- Calling on students to answer questions you pose, and engaging with students in a positive and friendly manner can help you build rapport and encourage students to work hard to understand the material.

- When lecturing, you can ask students, especially those who sit in the back, to help you check your volume by setting up a non-verbal system for students to communicate with you (i.e., have them cup a hand around their ear if they need you to speak up).

Presentation of Yourself

- Show enthusiasm for the material you are covering. Your enthusiasm, which can be conveyed through conversational language as opposed to formal language, can encourage students to also be excited about the material.

- Moving around the room and using open and natural gestures can convey that you are open to questions.

- Avoid being monotone by using your voice as a highlighter. Use emphasis on important words or concepts to signal to your students the importance of the idea. You can also imagine you are having a conversation with someone rather than lecturing. When conversing, we tend to have more natural inflections and changes in our voice.

Principles of Good Slide Design

When thinking about how to present information to your students, it is important to understand the cognitive structure of how students learn. The Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning helps explain the process in which students learn based on students’ cognitive load. Cognitive load is the amount of information a student can process at one time before moving on to new information. Below is a summary of Mayer’s principles for addressing cognitive load in multimedia presentations.

Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning

- Get rid of seductive details, or details that don’t help students understand the material (Coherence Principle).

- Use underlining, pointing, color, etc. to point out the most important points in a lesson (Signaling Principle).

- Don’t present the same information twice in a presentation, and/or don’t read text from a slide unless needed (Redundancy Principle).

- Introduce connected information close together, spatially, auditorily and temporally (Reducing Split Attention).

- Show complex information in steps, rather than all at once (Segmenting Principle).

- Introduce vocabulary terms prior to introducing how they work together in the lesson (Pre-training Principle).

- Narration with visuals help students more than on-screen text (Modality Principle).

- Present information in a personalized way by using second-person language, like “you” and “we” (Personalization Principle).

- Present recorded lessons with a human voice instead of a generated voice (Voice Principle).

- Encourage active learning in class by using generative learning strategies (Generative Learning Principles).

- Context matters: Use the above principles as a guide and in ways that make sense for your own classroom and topic.

- All images should convey meaning: when including images in your lessons, etc. make sure the information is relevant to the goal of the lesson.

- Allow time for processing: Students vary in the amount of time they need to process new material. Include stops throughout a class to increase learning.

- Teaching is dialogic: Encourage students to engage with you and the material to help them be active learners.

- Not all activities lead to active learning: Use activities that encourage students to connect new material with prior understanding for best learning outcomes.

Practicing Lecture

Practicing your lecture prior to class is incredibly effective in building your confidence while ensuring that the timing is appropriate. Here are a few things to consider when practicing.

- Prepare speaking notes that have all the content, but not a script to read from.

- Include delivery reminders in the notes and/or slides that are easy to see, such as visual or written cues to stop, breathe, drink, smile, ask questions, etc.

- Bring water/tea to soothe a dry throat and remind you to pace your speaking.

- Note common points of confusion or parts where students may have questions, and add in time to answer questions or to check understanding.

Using and Preparing Handouts in Class

Using handouts in class helps reduce the amount of cognitive load put onto students by helping them organize, structure and focus on the most important information. Additionally, handouts encourage students to actively engage during class and then be used as a study tool.

- Purpose: outline main idea, activate prior knowledge, assist with organization of the material, and reduce cognitive load.

- Examples: class outline, lecture slides (helpful to have a space for notes next to the slides), vocabulary lists, map, timeline, and guided notes.

- Examples from K. Patricia Cross Academy.

- Purpose: help students focus on important information and structure it correctly in their mental models, keep students’ attention, use as a way to ‘rehearse’ answers, and guide for small-group work.

- Examples: problems to solve, questions about readings, matrices or diagrams to fill in, and fill-in-the-blank notes.

- Examples from Oregon State:

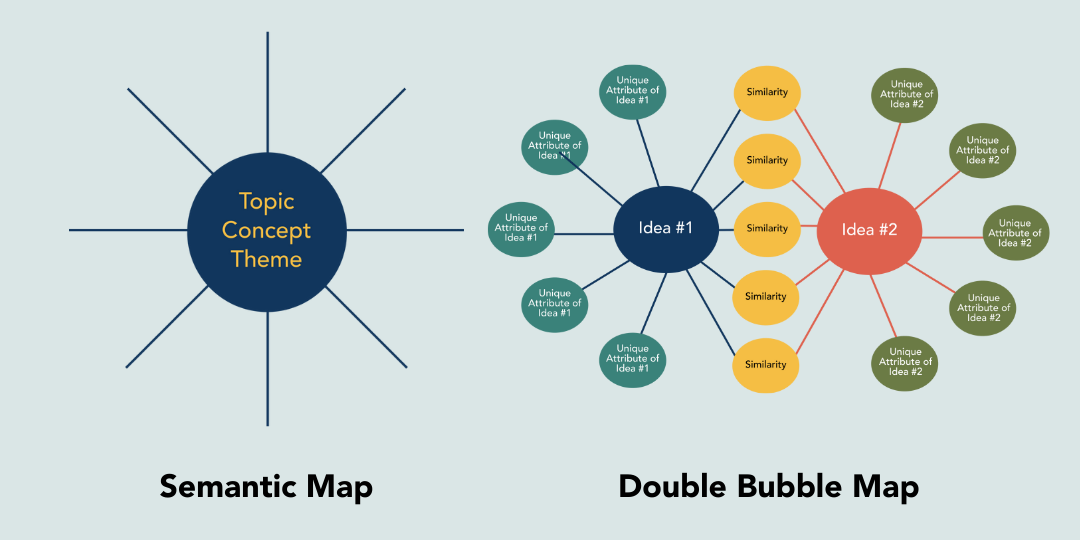

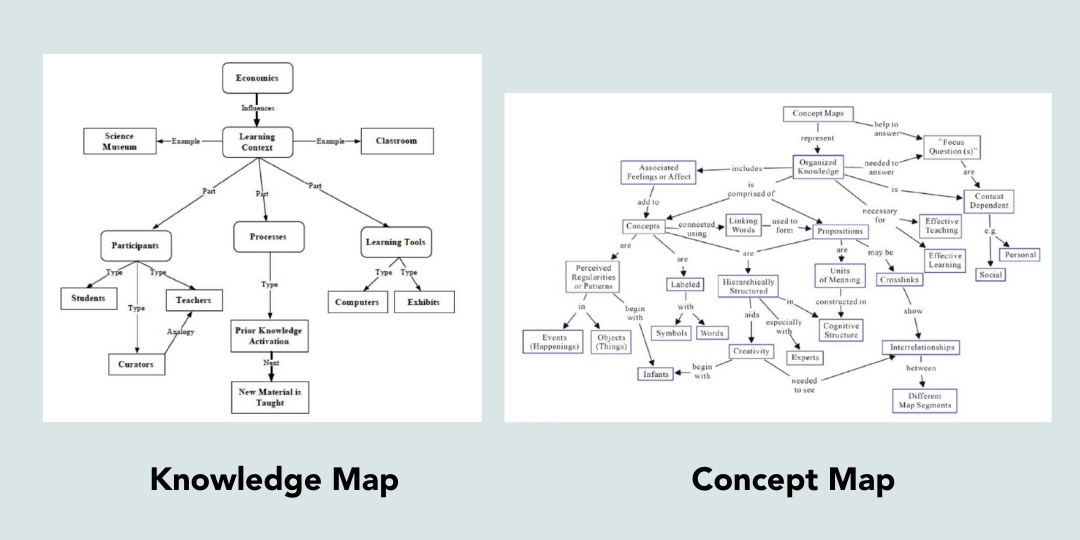

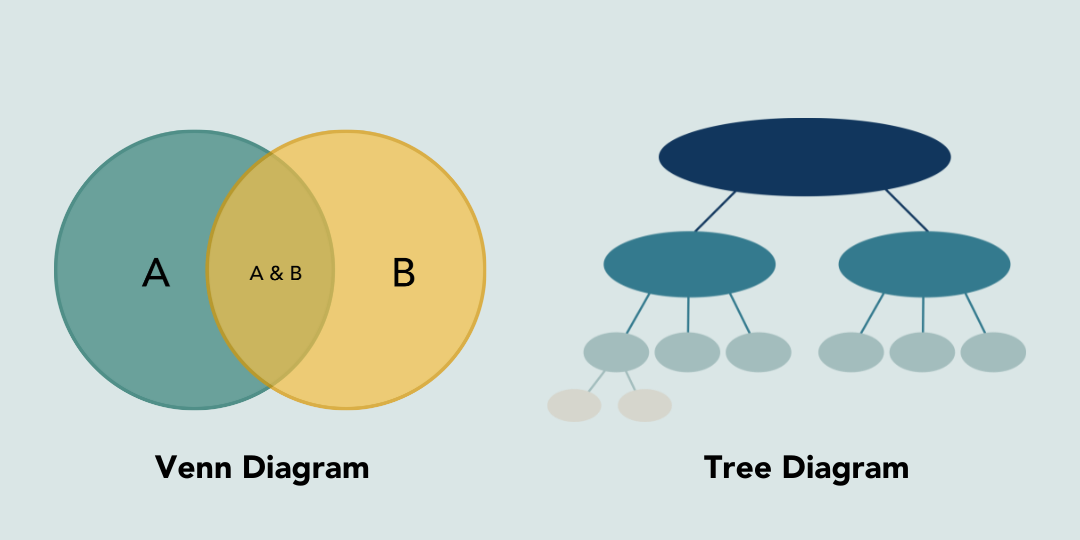

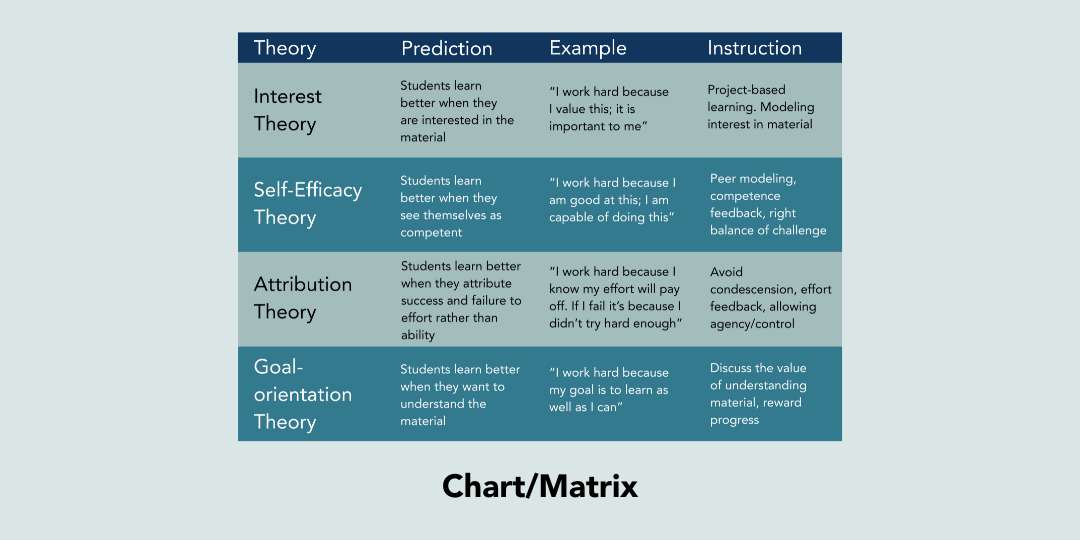

- Purpose: create a visual representation of relationships in the material, depict different structures and relationships material can take on, and active prior knowledge.

- Examples: semantic maps, bubble maps, knowledge maps, venn diagrams, charts/matrix, and tree diagram.

- Example from IRIS Peabody Vanderbilt

Resources

Mayer, R. E. (2014). The Cambridge Handbook of multimedia learning. Cambridge University Press.

Fiorella, L., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). Eight ways to promote generative learning. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 717-741.